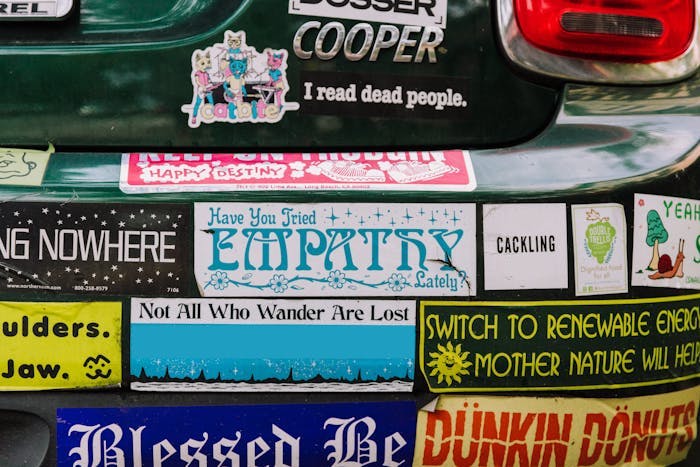

As a comedy writer, I’ve learned to expect ideas when I least expect them. The material for my ideas—the details and small interactions—to a comedian, these are gold. But learning to collect and consider these nuggets is also a key part of the essay-writing process.

Sentence x Sentence Dispatches from the Pursuit of Good Writing

“How in the world do I end this?” It's a common question from college-essay writers, and it emerges right when they reach for reflection. But not knowing your ending isn’t a liability. In fact, this state of not knowing can be exactly where you want to be.

When it comes to personal essays, even a good outline isn't a turn-by-turn map. Instead, offshoots and byways, unseen at the start, always crop up. Working with my Creative Mentoring student reminded me just how much wayfinding happens along the way.

Her email arrived thirty minutes before we were to meet. She wrote: "Attached is the same draft I sent you, but my parents had someone else look at it. The second version on the document was primarily written by my dad."

Julie sits in my office, fidgeting with her notebook. She sighs, and it’s so exaggerated we both laugh. She seems ready to talk, so I lean forward at my desk. I’m listening. “I know the story I should write,” she says, almost conspiratorially. “It’s just not the story I want to write.”

Somehow, it’s been almost 25 years since my undergraduate mentor, a beloved journalism professor, urged our nonfiction writing class out into the world to ask questions: If you go looking for a story, a story will happen. The phrase’s durability stems from its Zen-like acceptance of chance, of discovery. Stated: If you go, it’ll happen. Unstated: “It” might not be what you thought you were looking for.

After I bought my son his first set of good paintbrushes, the All-Knowing Algorithm spammed my social media with time-lapse videos of artists painting. As a writer, I can’t help it — I see metaphors for writing everywhere. I thought ... that's just like writing!

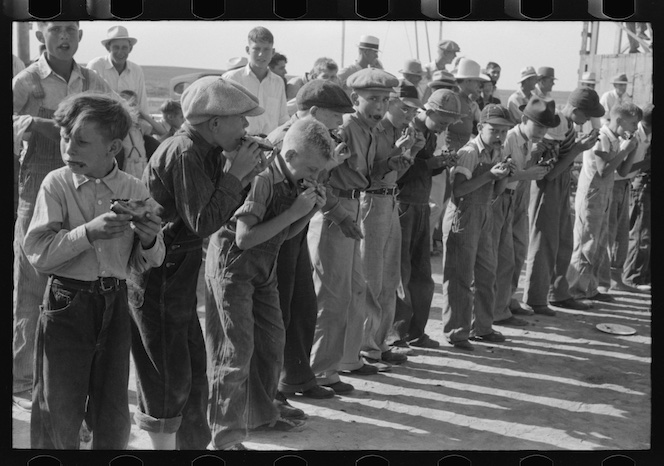

In eighth grade, I took an elective to prep for a yearly STEM competition. I was eager to build rubber-band-powered airplanes and roller coasters, but as we filed in on Day One, there were no materials or tools to be found. Instead, the teacher divided us into pairs. One of us had to describe an object, the other had to draw it.

I once helped a college applicant who wrote beautifully about a terrible place to swim. It was a stretch of bay marked by strong currents, stinging sea lice, and a pungent smell when the tide stole the water altogether.

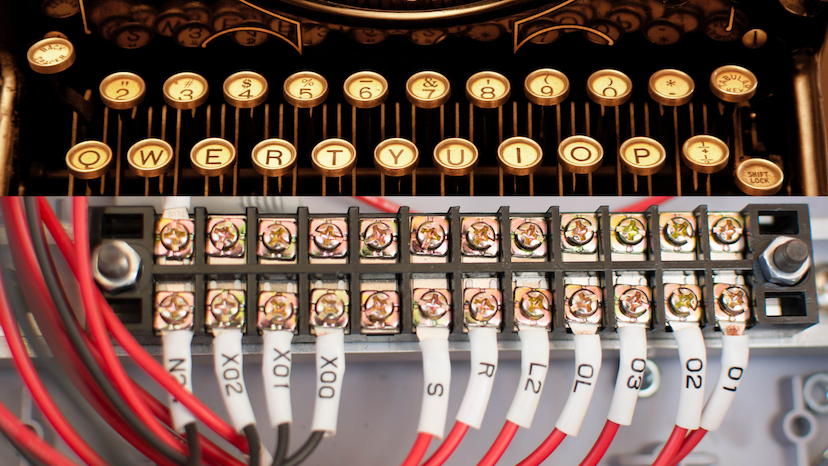

The lights of the theater dimmed and all I could think was, "Is this really a good idea?" From a young age, I’d believed I was destined for a different kind of performance. But here I was, at age twenty-seven, backstage at Improv Boston, about to perform a sketch comedy show. Three years later, I would quit my electrical engineering job to pursue writing and teaching full time.

I asked her to draw a map. This is something I do sometimes when a student tells me they have nothing to write about. I have them draw their hometown or a place they know well. I have them sketch landmarks and points of interest. No detail is too small. At this early stage in the writing process, our work is to deal with self-doubt by gathering possibilities.

At Hillside, we tend to ask a lot of questions, especially of college-application writers. If you’re talking about preparing for a robotics competition, then we want to know where your team gathered, what songs you jammed to while you drew the designs, and the fact that you nicknamed the robot “Sparky.”

' />

' />